Legend 07: An Englishman who served as a bridge between Japan and Europe, Sir Ian Gibson

Sir Ian Gibson

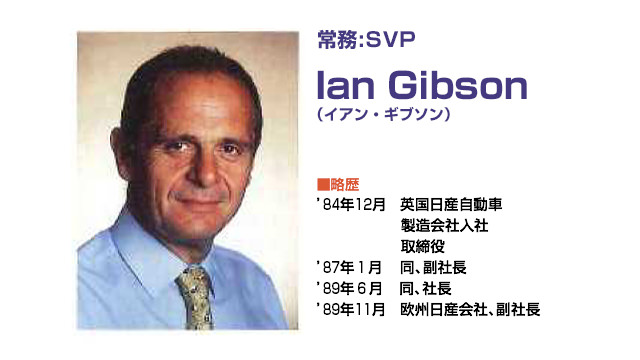

Sir Ian Gibson joined Ford Motor Company upon graduating from university. At Ford, he worked primarily in industrial relations and manufacturing management and rose to be general operations manager. He moved to Nissan Motor Manufacturing (UK) Ltd. (NMUK) in 1984 to be the director of the department responsible for purchasing and production control at Nissan’s new plant in Sunderland, in the county of Tyne and Wear, in North East England, which was just starting operations.

In 1987, he was promoted to chief executive of the department and from 1990 he concurrently served as the director of the Nissan European Technology Centre. In 1997, Sir Ian was made managing director of Nissan Motor Ibérica and in 1999 he was promoted to managing director of Nissan Europe and appointed the first ever non-Japanese executive in Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. He was made a Commander of the British Empire (CBE) in 1990 and knighted in 1999. After leaving Nissan in 2001, he assumed various directorships, including chairman of Trinity Mirror, the owner of the Daily Mirror. Sir Ian Gibson is currently(as of 2013) the chairman of Wm Morrison Supermarkets, one of the UK’s largest supermarket groups.

Introducing the Japanese management style into Europe

Before I interviewed Sir Ian Gibson, I was told by a chorus of people who knew him that choosing Gibson was an ‘absolutely excellent choice. He deserves to be featured as a subject in this series of biographies.’ These personal testimonies were very encouraging for me as I prepared to conduct an interview with someone I had never met in person because I was going to have to do it entirely over the phone between Japan and the UK due to scheduling difficulties.

Sir Ian joined Ford Motor after he graduated from university and he worked mostly in industrial relations and manufacturing management at the American automaker, where he spent about 15 years. ‘I was hoping to work for either a carmaker or an aircraft manufacturer,’ he said. ‘It was a difficult call, but eventually I decided on the auto industry. You can’t own an airplane, so I thought making cars would be much closer to daily life,’ he recalled with a laugh.

In 1984, he moved to Nissan Motor. It is not unusual to switch companies in the auto industry, but what was it like for a Briton who had worked for an American company to change to a Japanese carmaker?

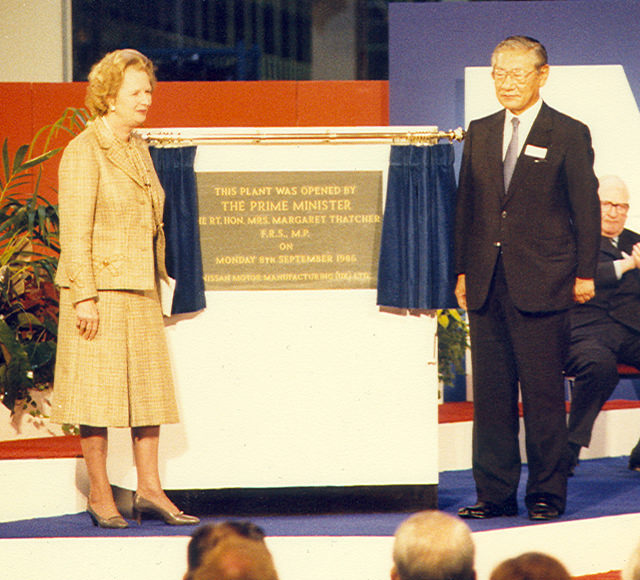

In 1984, Sir Ian, just entered Nissan Motor Manufacturing (UK) Ltd., Sunderland plant.

In November 1984, the time starting the construction of Sunderland plant.

‘I was working in Germany, Spain, and the UK in the second half of the 1970s,’ he said. ‘We worked with Mazda on a number of occasions around that time. Back then it was considered difficult to apply Japanese-style management directly to Americans or Europeans, but Nissan was about to tackle this very issue. The determining reason that I moved to Nissan was that I thought my experience of having worked with Mazda might prove helpful. However, after I joined the Japanese company I realised that, in the end, my experience of having worked with Mazda was rather like having watched a football match or a baseball game from the stands as a spectator.’

According to him, although the first couple of months passed without any major problems, he eventually was struck by culture shock as he lived through many different situations. ‘I experienced many different forms of culture shock and one of them was the extremely vague decision-making process. In Western culture, when a decision is being made about something, all of the staff members concerned with the matter meet in one place, voice their opinions in turn, and then make the final decision. When something is to be decided in a Japanese company, a thick fog appears all of a sudden and settles over everyone and you are at a loss as to what is happening, then the fog clears and it turns out that everything has been decided.

Learning from the differences in corporate culture

‘Another element of culture shock arose from differences in corporate culture. The Japanese employee is deeply respectful of his superiors and of people with knowledge and/or experience. Young people are not directly taught what to do by their bosses. Instead, they have to learn how to do their jobs by watching how their superiors do their jobs. On the other hand, Westerners place great importance on the transfer of knowledge. Superiors have a responsibility to pass on their knowledge and experience to younger people. To do this, they train their subordinates directly. Young people in the West take it for granted that they will be taught in this way and as a result, younger employees were feeling frustrated and wondering why their superiors weren’t teaching them.

‘It’s a difference in thinking about what leadership is. Young Western employees wanted their relations with their Japanese superiors to be on an equal footing, the way they are with Western bosses, while the Japanese leaders were unhappy because they felt that the young employees weren’t really listening to them. I found myself explaining this cultural difference to both Japanese and Western people through late 1980’s.

Personally, I felt that learning about different cultures was essential in upgrading my own thought patterns. So it was a lot of work, but I enjoyed tackling it.’

The Japanese staff were at pains to learn Western ways and the Western staff worked hard to understand Japanese ways. Sir Ian said that a positive atmosphere gradually started to set in as people worked to solve the problems together by learning from each other. ‘In particular, I found the concept of kaizen to be outstanding at the gemba and I was also very impressed by the operational approach to viewing the gemba, understanding it, and thinking about things at the level of the gemba. We as Westerners learned a lot from Japan.’

Integrating the superior aspects of Europe and America on the one hand and Japan on the other became the Sunderland way and this approach later spread to Germany and Spain and finally to all of Nissan’s subsidiaries in Europe.

The Sunderland plant is where Sir Ian spent most of the heyday of his career. I heard that the corporate loyalty of the British employees was so high that some went on business trips abroad wearing plant uniforms. Sir Ian is still in touch with staff members with whom he worked at the plant. What does Sunderland mean to him?

‘I have many memories, both of good times and of difficult times. It was my family, my child, and at the same time it was like university,’ he said. ‘I hired many young people while working there. They are now in their 40s and 50s and have assumed important positions in the company. Some have become board members. I’ve known them since they were young, so I feel like they are my children and I’m their father and they are like my family. I wish them even greater success.

‘I learned a great deal at Nissan. It was more like going to school every day rather than working in a company. There were tough times and good times. But everything was very challenging and I was able to deal with many issues in a positive way.’

Having learned what a Japanese company was and how things worked there and having become proud of working at the company called Nissan Motor, Sir Ian was later to be part of a team charged with carrying through a historic project.

The Nissan brand triumphs in Europe

From the second half of the 1980s to the first half of 1990s, Nissan grew substantially in Europe. The good news kept coming, with one success after another: there was the successful launch of the Primera, the first model produced in Europe; the establishment of Nissan Motor Great Britain (NMGB); and the introduction of the Micra (the March in Japan) in the European market and the Micra’s winning of the European Car of the Year award in 1993.

Sir Ian Gibson recalls, ‘At the time, Nissan sold in 16 European markets and Nissan’s positioning and brand image were slightly different depending on the market. In some markets in Europe the numbers of cars imported from Japan was limited and it was virtually impossible to grow our shares meaningfully. However, the full-scale operation of the Sunderland plant made it possible to supply the products from the UK, which gave us an opportunity to establish a common brand image throughout Europe.

‘At the same time, we worked on rebuilding our dealer network. It was a fairly complicated task because many European dealerships were family run, but we started to tackle the issue seriously in late 1993 and rebuilt the dealership network country by country.’

Sir Ian Gibson, photographed with a car as commemoration.

Despite these successes, Nissan would find itself facing an unprecedented crisis within a few years. As Sir Ian explained, ‘In the second half of the 1990s, I started to see a growing mismatch between our actual unit sales and our marketing strategies and our profits began to decline. We had to address this issue and so we immediately put kaizen practices into place. First we looked to cut production costs and invest the money that we saved in marketing. Normally, cutting costs per se is not that difficult as long as unit sales are on an uptrend, but at the time Nissan’s unit sales were flat, even after our rationalisation of costs. However, we had no choice but to continue with that strategy. We tried to reduce costs further by implementing a platform strategy and improving our production lines. There was no magic bullet that could reverse the situation overnight, but we tried to weather the storm of adversity through the cumulative effect of many small improvements.’

In 1999, Nissan Motor formed an alliance with Renault. Sir Ian was at the forefront of the Alliance as the president of Nissan Europe and as the first non-Japanese senior vice president at Nissan Motor Co., Ltd.

PRIMERA

MICRA

Will be the basis for the company's future success

‘When people started to talk about the possibility of an alliance, I was the managing director of Nissan Motor Ibérica in Spain and living in Spain. One of the names raised as a potential alliance partner was Mercedes-Benz, in addition to Renault—many years have already passed since then, so I can talk about it now—but I personally thought it would be difficult to work with Renault. Of course, there was the fundamental problem of me being British and them being French (laughter). Another factor was that the French auto industry did not have a very favourable view of the Japanese auto industry at the time.

‘However, when I talked to the people at Renault in person, I was very surprised. They were very open and they made it clear that they thought they could learn a great deal from Nissan and were eager to do so, although, of course, as one would expect, there were some people at Renault who were against an alliance with Nissan. As the negotiations progressed, I personally came to have a very positive view of this possible alliance because I felt that we could build favourable relationships and I thought that it would benefit Nissan from the perspective of sales strategy. Back then, Renault had a 12% market share in Europe, while Nissan had only 5%. I still believe to this day that this was the right Alliance, because it united these two companies.’

In 2012, 13 years after the formation of the alliance, Nissan recorded the top shares among Asian carmakers in the UK, Spain, France, Portugal, and Belgium. What does Sir Ian, who has now left the company, think Nissan’s strengths are? ‘Its strength lies in the rational values of its products,’ he told me. ‘Nissan products are consistently marked by quality, reliability, durability, economy, and product power and these attributes have won it the support of its customers. Recently, an emotional value is being added to this list of attributes. I can see more European taste in the company’s designs and engines and I presume that these features are among the reasons for the success of Nissan’s cars.’

Sir Ian says that today’s success will be the basis for the company’s future success and that all of the people who are involved with Nissan should pay attention to this fact. ‘Nissan has established its brand in Europe over the course of a quarter of a century, since the launch of the Primera in 1990. This fact is what people at Nissan should be proud of. It has taken easily 100 years for the European car manufacturers to establish their brands, but Nissan has accomplished this task in only a quarter of that time. It’s an amazing accomplishment and I wish Nissan even greater success in further consolidating its presence over the next 25 years.’

Sir Ian Gibson was a polite and courteous interviewee and chose his words carefully. Although I could not see him, our conversation gave me more than ample proof of his charm and magnetism. I could not help but think that the people who had an opportunity to work with a leader like him were fortunate. I had neither met nor spoken with him before, but by the end of the telephone interview, I felt as if I had known him for quite a long time.

Profile of the writer

Shintaro Watanabe

Born in 1966 in Tokyo. After graduating from a university in the US, he worked as an editor of Le Volant, an automobile magazine, before joining Car Graphic’s editorial staff in 1998. He left Car Graphic in 2003 and became a representative of MPI, an editorial production company, while also working as an automotive journalist. He also works as a chief editor for Car Graphic.