Legend 06: Hailed as a ‘Pioneer’, Kyoko Shimada

Kyoko Shimada

Kyoko Shimada grew up in Tokyo. She joined Nissan Motor as a designer in 1967 after graduating from the Japan Women’s University with a major in architecture. She worked in various fields, including product planning, a corporate identity project, sales planning, public relations, corporate citizenship activities, and corporate social responsibility (CSR).

After she retired in 2005, she served as a director, secretary general, and part-time lecturer at the Japan Women’s University. Since September 2010, she has been the representative director, director general of the Yokohama Arts Foundation. She has also held various other positions in society, including serving as a member of the Central Council for Education of the Ministry of Education, the chairperson of the CSR Committee at Keidanren, and a director of a nonprofit organisation, among others. As a pioneer of female participation not only inside Nissan but also in Japanese society, Kyoko Shimada continues to be very active and to attract attention for her influence on society.

What Nissan's first female designer felt

During its 80-year history of progress and development, Nissan has undergone a number of major transformations, including among others the hiring of female designers ahead of the demands of the times so as to utilise their unique capabilities, the execution of a global brand strategy based on corporate identity initiatives, and the transformation of sales activities from door-to-door sales to sales at dealer showrooms.

Kyoko Shimada was one of the key players taking on the challenges involved in these far-from-minor reforms and often she served as the leader of these efforts. Having read this far, many readers may be surprised by this and surprise can be considered a natural response.

After all, the stage was an automaker and even though Nissan has always been characterised by a relatively liberal and pliable corporate culture, it was undisputedly a male-dominated company, as was the case with other automakers around the world. It is fair to say that Kyoko Shimada’s career overlaps with the history of challenges at Nissan and with the history of the advance of women in the automobile industry.

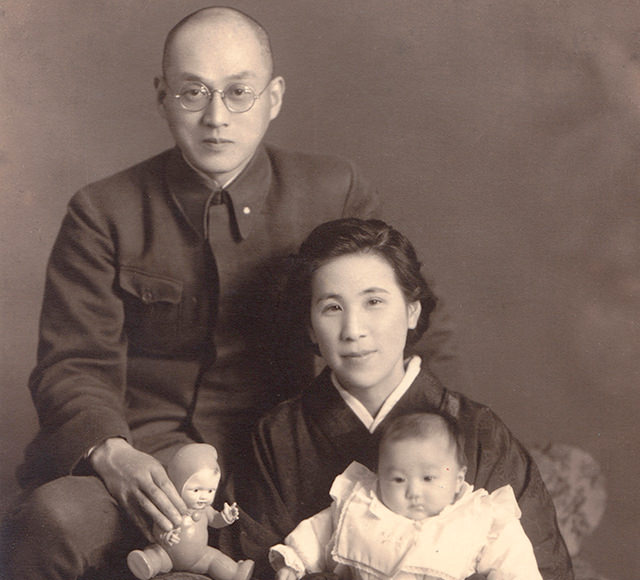

Three months after birth with her parents, at the capital of Manchuria (May, 1945).

At a graduation ceremony of Japan Women’s University with her friends of architecture subject (March, 1967. Shimada, 2nd person from right side).

‘To tell you the truth, when I joined Nissan, I thought I’d only work there for two or three years. I meant for it to be a temporary job,’ she confessed.

Since we are very familiar with her role as a pioneer in subsequent years, these words of hers are quite surprising. But her determination to be true to herself was the driving force behind her outstanding career, which in turn contributed greatly to the development of Nissan into a global company.

She was born in northern China six months before the end of World War II and grew up in Tokyo, where she studied architecture at the Japan Women’s University. Despite her major, she decided to work at Nissan as she thought ‘it wouldn’t be a bad idea to experience a different world before becoming an architect.’ She was employed as a designer.

This was in 1967, which was still 19 years before the Equal Employment Opportunity Act for Men and Women took effect in Japan and a time when women’s active participation in all areas of society had yet to take root in Japan. Shimada recalls, ‘There wasn’t a single female designer at any of the automakers in Japan at that time, but Nissan recognised ahead of other car companies that it was necessary to get a woman’s input into car design because every household was about to own a car.’

Shimada started off her career as the first female designer in the Japanese auto industry.

If there is no precedent, why not make one?

It was a time when the car was a symbol of Japan’s post-war reconstruction and high economic growth, as well as an object of desire among the public. Most of her co-workers, including engineers and peers in other departments, not to mention a staff of around 50 designers, were men who were well versed in automobiles. Despite finding herself in this environment, Shimada was not particularly interested in cars as advanced machinery operated by drivers.

Instead, or rather, because of that, she had unique strengths that her male colleagues lacked. ‘Living space’ is how she saw a car. It was a living space that also had a function of mobility, a space for not only the driver but also the passengers in the front and rear seats, as well as other elements, such as contrast and harmonisation with the outside world. Shimada also considered a car to be a space where the users themselves could express their own lifestyles and identities.

Shimada was assigned to work on colours and interior designs for passenger cars. Trying to get some inspiration, she browsed around department stores to get a feel for what was in for not only women’s but also men’s fashion and colours and visited various places to see sophisticated and bijou buildings and furniture.

She proposed chic blues, browns and whites at a time when the exteriors of official luxury vehicles were all black, casually challenging stereotypes that nobody had ever before thought of questioning.

Looking back on that time, Shimada said, ‘I often hear people saying “because there’s no precedent.” But having no precedent can’t be an excuse of not doing something differently. If there is no precedent, why not make one? Once there is a case, others will follow in a natural way.’

She feels that her way of approaching things might have been influenced by her training in the creative field of architecture, as well as her own experiences at Nissan. But that’s not all. She added, ‘Ever since I was a little girl, I was never obsessed with winning competitions. Instead, I always thought that I would do something that only I could do, even while always being aware of the role that was expected of me.’

As she devoted herself to her various assignments, she formulated the idea of ‘getting more involved in car development from a broader perspective.’ In time she was transferred to the Design and Development Division. For her, who had no expertise in this area, it was a major career change that amounted to starting over from scratch. It was indeed challenging. By then, seven years has passed since she had joined Nissan, which she had considered a temporary arrangement.

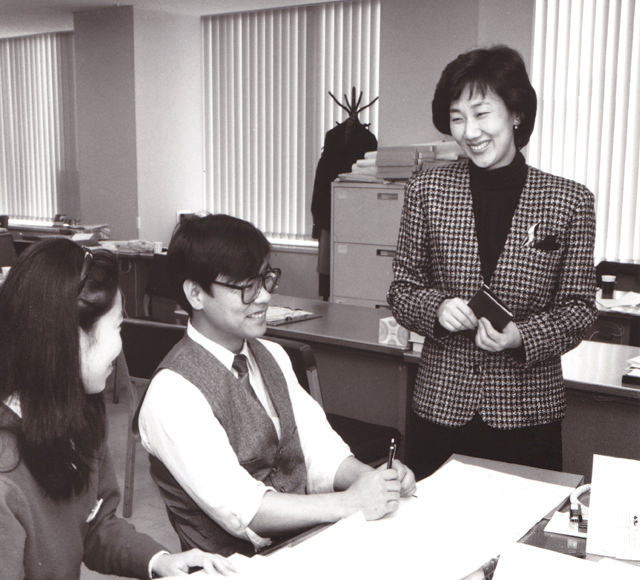

Enriched experiences in the totally new field of the Design and Development Division following her first assignment at the Design Department (at the Head Office Showroom).

In the vanguard of brand strategy execution

In 1974, her eighth year at Nissan, Shimada was transferred to the Design and Development Division, where she devised new products based on the findings of market research. There was one thing in particular that she had noticed while watching generations of Nissan products roll by as part of her work. The logos and badges were all different from one model to the next and the colours and typographies of dealer signboards, product leaflets, and product brochures were all different. She began to ask herself, ‘What is Nissan-ness?’ ‘Perhaps it’s time to consider a global brand strategy for a new era?’

On a business trip to New York, the first overseas business trip by a female employee at the time.

In 1980, she was given an opportunity to go overseas to learn more about this issue. Soon after, in 1981, she was named one of five members of a corporate identity (CI) project team that would report directly to the president of the company. The project’s mission was to complete the development and preparation of a plan and manual to promote the CI initiative in two years. She was selected to be in the vanguard of this major transformation. After the project team was disbanded, Shimada was transferred to the Communication Department to continue working on the global deployment and execution of the CI plan.

‘To me, a unique feature of Nissan-ness is a willingness to take on challenges. Because of that, Nissan encourages freewheeling thinking and can build forward-looking cars that respond to the needs of a new era. The CI initiative provided a great opportunity to embody this challenging spirit.’

In later years, her experience took her to the mission of developing VI (Visual Identity) as part of the company’s global brand strategy. During her time in the Communication Department, Shimada was involved in image creation strategy and in 1984 she was named the first female manager at Nissan. Moving to the Business Planning Department in 1988, also as a manager, she took charge of the renewal of dealer showrooms nationwide. This signalled a major shift in sales style from traditional door-to-door sales to new showroom-based sales activities.

She visited many overseas facilities, mainly in Europe and North America, to promote the global deployment of the CI initiative.

‘Conventional dealers that mainly sold cars through door-to-door visits were just displaying cars and as such were far from generating a welcoming atmosphere for customers to simply drop in. I thought that dealers should be transformed to accommodate the needs of family users and to welcome female drivers, whose numbers were rising sharply from the early 1980s. My ideas were translated into the establishment of casual café-like spaces and children’s play areas, as well as the renovation of bathrooms into clean, comfortable spaces. Feminine wisdom and a designer’s perspective helped me greatly.’

In 1991, Shimada was put in charge of corporate citizenship activities. Realising the importance of such activities, many companies today conduct related programs constantly and systematically as an essential part of their business strategies. Back then, however, few businesses in Japan considered such social programmes a valuable part of their social roles and promoted them accordingly. Nissan was the leader among automakers in this field. Some argued the necessity of such programmes because the Japanese economy was then facing extreme difficulties and the business environment was quite daunting, but Yutaka Kume, Nissan’s president at the time strongly believed that corporate citizenship activities were critical business issues for every company and intimately connected with a company’s raison d’être in society. Under his leadership, a dedicated section was established at Nissan and Shimada was put in charge of it to ensure its success.

‘In a world where global society and Japanese society are constantly changing, we can see that societies based on monolithic value systems are fragile. I believe that a society that accepts different value systems and a society where the interaction of diverse values takes place can serve as an incubator for powerful forces that will lead to the building of new societies.’

I like working with people

Awarded the Japan Mécénat Award by the Association for Corporate Support of the Arts, which honours corporations and corporate foundations for outstanding arts support (Shimada, 1st person from left side).

A society encompasses too many problems for a single company to cope with. In order to define a clear direction and translate it into a business strategy, Shimada developed a course of action and adopted criteria for choosing an area of activities and groups to support.

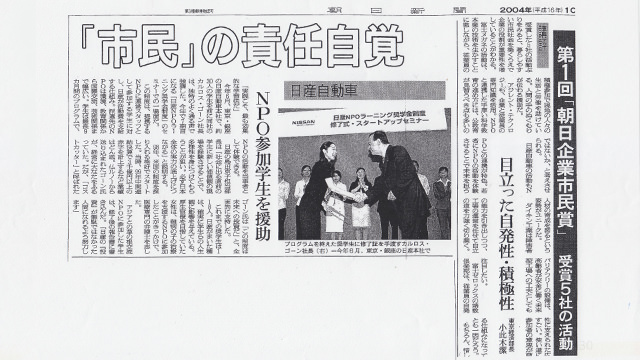

One of the company’s unique corporate citizenship activities is the Nissan-NPO Learning Scholarship Programme, under which Nissan recruits and selects students to work at NPOs and provides them with scholarships commensurate with their internship activities. ‘This programme was launched in 1998 in the hope of providing young people with an opportunity to engage in intellectual labour.’ Referring to it as ‘investing in the young’, Nissan’s CEO handed out certificates to the participants each year.

Another initiative called the Nissan Children’s Storybook and Picture Book Grand Prix has entered its 29th consecutive year, serving as a gateway to success for young authors.

Among other examples of Shimada’s work and expansion of corporate initiatives, she promoted taking diverse ideas from society into the company and encouraged various volunteer activities among employees by providing corporate support.

In 2003, when the CSR concept was not yet widely recognised in Japan, Shimada was ordered by CEO to establish a project team to compile and issue a sustainability report. As the project leader, she set up the Sustainability Group within the Public Relations Department and it became the foundation of today’s CSR initiatives at Nissan.

‘In fact, during the course of compiling the report, I came to believe that CSR could be a means of corporate governance. I see sustainability as a broader concept. Sustainability can help us review and re-evaluate all corporate activities from the viewpoints of all stakeholders and help us encourage employees to develop a social perspective. Compiling the report led to the identification of common ground shared by the company and society, which can secure sustainable growth. I think that a constant dialogue with society can make the company an organisation that is always learning.’

The key words for the corporate citizenship activities and CSR initiatives to which Shimada devoted herself were ‘diversity’ and ‘a learning organisation’. They are key words that reflect the present times, that symbolise Nissan constantly taking on new challenges, and that mirror the personality of Kyoko Shimada.

‘Because I myself do not have particularly high competencies, I cannot move forward without support from experts around me. From the time that I joined Nissan until I retired, I kept learning from others.

‘My days at Nissan made me realise that I like to work with people. When different personalities get together, they teach me things that I was not aware of and I often have ideas I could not have come up with on my own. I am also impressed quite often by the different thinking and feelings of others.’

A newspaper article covering the awarding of the First Asahi Corporate Citizen Award.

She spent 38 years at the company she joined with the idea that it would only be a temporary arrangement, staying until she reached retirement age. She pursued her assignments quietly and steadily and along the way, she established a record of achievements that invariably are qualified with such words as ‘the first woman’ or ‘the only woman’.

‘Of course I got frustrated. But when I think about it now, I know that I gained more than I lost. For instance, I was given a chance to try something new because they thought “a woman might bring a different sense and different abilities from a man”. Creating a precedent by myself was an exciting experience.’

Kyoko Shimada was always a pioneer, not only at Nissan but also in the Japanese automobile industry. Since retiring from Nissan, she has remained active as a person who is fond of working with people, assuming the posts of executive director of the Japan Women’s University and representative director of the Yokohama Arts Foundation, which operates 13 art-related facilities.

Shimada gave interview.

Profile of the writer

Sayuri Oka

Sayuri Oka is a writer and editor who was born in Tokyo. She graduated from the College of Literature at Aoyama Gakuin University and became a high school teacher before joining Nigensha in 1990 as an editorial reporter for NAVI, an automotive magazine. Since 1995, when she became a freelance writer and editor, she has taken advantage of being a woman, a mother, and a housewife and written various articles about automobiles and other topics. Her activities cover a wide range of fields, including producing the official website of a university and advertisements.