Legend 05: Giving life to the factory, Tadao Takahashi

Tadao Takahashi

He was involved in the launch of the casting workshop at the Tochigi Plant upon joining the company and eventually was named the head of the Lerma plant in Mexico, in 1983. He was responsible for closing the Zama Plant in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1992 as the deputy head of Technologies Department 1. Before resigning in 2009 and assuming directorships at various external organizations, Takahashi became a senior vice president in 1998, was promoted to executive vice president in 2002, and was named vice-chairman in 2007. He was awarded a Medal with Blue Ribbon by the Japanese government in 2012 in recognition of his contributions to society.

I want to build manufacturing plants overseas

An automobile company encompasses indeed a wide range of jobs, from designing and engineering through producing and selling automobiles to advertising, marketing, and publicity. Despite this range of activities, carmakers are classified as belonging to the manufacturing sector. A carmaker’s main business is the production of cars and Tadao Takahashi was engaged in production for almost 40 years, from his first days in the company.

Takahashi was born in Fukuoka Prefecture in 1945 but he spent most of his life in Tokyo until he graduated from university. After his graduation from the Department of Industrial Mechanical Engineering in the Faculty of Engineering at Tokyo University in 1968, he joined Nissan Motor. However, he has confessed that he did not have any particular passion for cars.

In this series of life stories, we have seen a strong passion for cars in all of the Nissan personalities that we have introduced, with this passion serving as the common driver moving them to join the automobile industry. So what made Takahashi decide to work for a carmaker?

Takahashi interviewed with several companies before he decided on Nissan Motor. During his first interview with the company, he said that he wanted to launch a plant overseas when asked what he would like to do in the future.

‘You can see how young and naïve I was to say something grandiose like that at the first interview (laughter). The interviewer then said, “I see. Would you mind going to a rural area?” I’d made my statement but I didn’t know much about plants and I didn’t even know where Nissan plants were located. So in fact I didn’t understand what the question meant when I answered, “No, I wouldn’t mind.”’

Takahashi was assigned to work in the Preparation Office set up in Kaminokawa, Tochigi Prefecture, where they were preparing to launch a new plant to be built there. Takahashi was the only freshman that year who was assigned to work there. ‘Despite having said that I wanted to launch a plant, I was worried about being the only freshman there and I had no knowledge whatsoever of construction,’ he recalled.

At the beginning he only followed the lead of his senior colleagues because he had no knowledge or skills that he could use for work. The only real work he had took place during lunchtime. ‘All the employees played softball during lunchtime. The property was so huge that we had to get out to the field in a minibus. I was the only rookie so I had to go to the site before the others and get everything ready, like putting out the bases on the field. It was the only time I was appreciated,’ he said with a laugh.

In 1969, the aluminum casting workshop began to operate on a full scale.

Cast aluminum ashtray made as a remembrance of Tochigi Plant’s inauguration. It was first work for Takahashi.

Takahashi spent 12 years at the Tochigi Plant and then was assigned to work in Mexico in 1980. ‘I had told headquarters that I wanted to work overseas and I thought the opportunity would arise earlier. So the announcement was welcome; it was something I had waited a long time for and it finally came.’

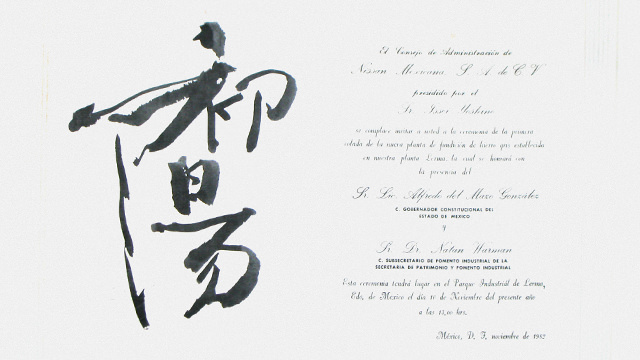

The Lerma Plant in Mexico was already in operation and Takahashi was assigned the job of constructing a second iron casting shop. Takahashi was one of only two Japanese staff at the time, with the rest local employees. After two and a half years construction had finally been completed and Takahashi was quietly waiting to hear that he had been transferred back to Japan, because he understood that his assignment in Mexico was to last around three years. However, he received the news that he had been promoted to section chief.

‘At the same time I was told to stay at the Lerma Plant as the head of the facility. I was 37 years old. I always worked in plants but I had no experience as a manager. I decided that I had to accept the assignment and that I would have to work hard and learn because I was going to be doing totally different kinds of jobs from what I had known before. I’m not certain if I achieved results that I can be proud of.’

With colleagues of Lerma Plant (Takahashi, 3rd person from right side).

He spent a total of six years in Mexico—the last three years as plant head—and went through a process of repeated trial and error in learning how to lead the highly individualistic Mexican employees. After his return to Japan, Takahashi served as production section chief at the Tochigi Plant and deputy head of the Engineering Work Department and deputy GM of the Casting Technology Department at the Yokohama Plant.

‘It had been 24 years since I’d joined the company. I’d always worked in plants and almost always with casting, but of course I had the ambition of working as a plant head in Japan and I was content to be working in a plant and thought that I would be happy to work in a plant my whole life.’

But in 1992 something happened that took even Takahashi by surprise. At the age of 47, he was called to work at company headquarters.

Integrating the strenghths of the individual plants

For Tadao Takahashi, who had expected to dedicate his entire career to production facilities and technologies, the transfer to headquarters was a bolt out of the blue.

Mr. Takahashi gave interview.

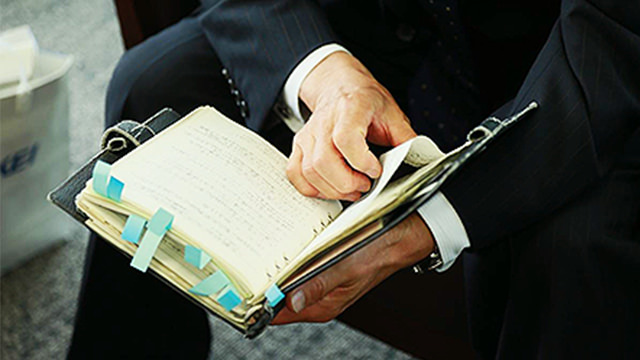

Takahashi’s personal notebook. He kept it always with him and in the 90’s, he has been writing the ideas for Synchronized Production.

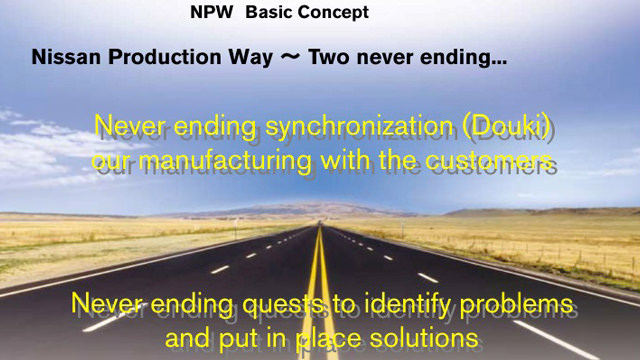

It was ironic that the first assignment at headquarters for Takahashi, who had always endeavoured to launch plants, was the closure of a plant. Nevertheless, this experience proved to be a trigger that led him to confront a variety of problems that had become entrenched in Nissan Motor’s production system. He recalled, ‘It was a difficult time for Nissan and all those experiences made me ponder why things had reached that state and conclude that we had to do something about it. Many people in the company became strongly aware of the problems and in 1994 we decided to create the Nissan Production Way, NPW.’

Takahashi says that production technologies, site management, and the production management of individual plants were excellent without exception when looked at plant by plant, but somehow the whole was less than the sum of its parts and the overall power of the company’s production system was not so great. The NPW concept was to aggregate and integrate the strengths of each plant into a stronger whole.

‘As they worked hard and competed with one another Every plant had distinctive characteristics. However, we lacked a system whereby each effort contributed to making the whole stronger,’ he analysed. ‘Then we learned not only the strengths of Nissan but also the advantages of outside entities and put them in one basket to create the first NPW concept. It was meaningful enough for us to create the Nissan Production Way as a shared concept for all employees, after a series of spirited discussions.

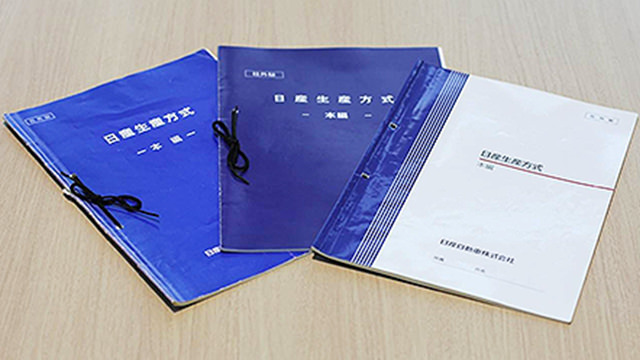

Booklet of NPW repeatedly revised and reprinted in 1944, 2000, and 2006.

Global development conference of Synchronized Production at Smyrna Plant in USA in 1997.

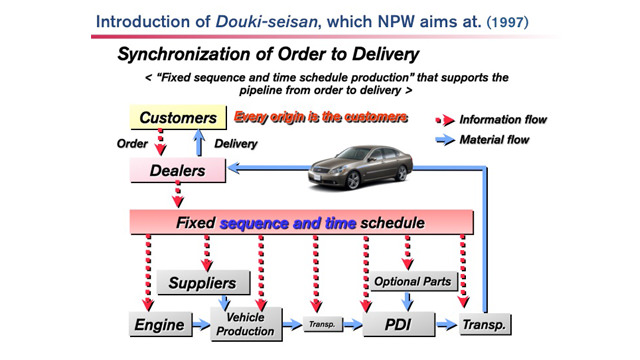

‘In 1997 “Synchronised Production” was initiated in the belief that a specific picture of goals was necessary to promote reform activities involving overseas plants, parts and components suppliers, and distributors. The Nissan Production Way with Synchronised Production as its core became the pillar of the manufacturing division in the reform of Nissan originating from the Revival Plan in 1999.’

Before the name NPW saw the light of day, Nissan deployed so-called “ANSWER” as an integrated production-sales management system. The system received customer orders from dealers daily and these were fed into production plans. Takahashi found it to be a good system, but it was only a system for helping with production planning.

‘Through ANSWER, a production plan based on customer order to establish the production sequence and the completion time of each vehicle to be manufactured four days before the completion of the vehicle was made. But it was in reality not working. Synchronised Production in a way is an essential idea that strictly complies with the plan produced by ANSWER. We established as the key indicators the rate of compliance with the planned schedule and the rate of compliance with the planned production sequence. This was not only carried out within the Nissan vehicle production lines but also transmitted to all of our suppliers and distributors took part and followed the same procedures. It was the beginning of Synchronised Production.

In the early stage it was very difficult. Only around 20% cleared the flow rate. Not only at suppliers and distributors but also at Nissan plants sequences and schedules were disrupted by such as breakdowns, poor quality, and management or control errors and any issues were identified. The most important point of Synchronised Production is that any issues in everywhere around the world are visualized on a daily basis. When they become “actualized,” we can improve the situation and collect know-how. I hear now that the efforts of many people have pushed up compliance rates close to 100% at many plants around the world.’

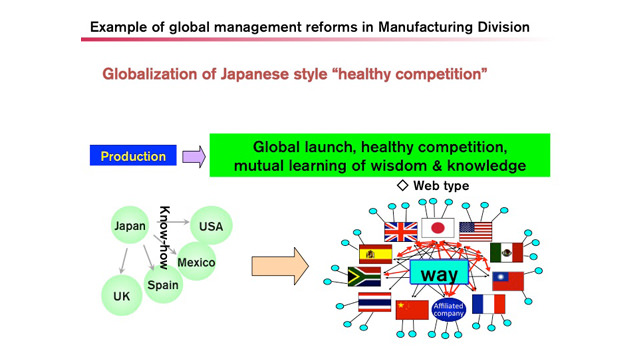

As for the globalization of NPW, the method to transmit know-how evolved from Japan centric to “web” style.

Made by Nissan

Production technologies are constantly advancing and plants are becoming modernised at a rapid rate. I wonder if automobile plants will be fully automated in the future so as to strictly observe the planned sequence flow and schedule as well as to stabilise product quality.appreciated by consumers in all of the markets around the world and if we want to keep getting better.

Takahashi says, ‘I think that automation will play a greater role in production if the structure of electric vehicles becomes simpler and automation technologies themselves make more progress. However, constant kaizen efforts and quality improvement are essential if we want to produce cars that are appreciated by consumers in all of the markets around the world and if we want to keep getting better.

Profile of the writer

Shintaro Watanabe

Born in 1966 in Tokyo. After graduating from a university in the US, he worked as an editor of Le Volant, an automobile magazine, before joining Car Graphic’s editorial staff in 1998. He left Car Graphic in 2003 and became a representative of MPI, an editorial production company, while also working as an automotive journalist. He also works as a chief editor for Car Graphic.